You can read the first 10 weeks of Jonathan’s marathon training journey via links further down – and support his chosen charity DEBRA, at this page.

Growing up, my cousin Mark suffered with Epidermolysis Bullosa (EB), a condition where the skin blisters easily.

My Auntie Di, who was also born with EB, would burst their blisters at the end of each day and wrap the resulting wounds in bandages. It must have been agony. Yet he would not let it hold him back.

“It took longer to do Mark’s dressings and blisters than mine: like me, he had dystrophic EB, but he had it a lot worse,” my Auntie tells me. “If you don’t burst them, they get bigger, just spread and spread… then when you do pop them, they’re more open to infection.

“As you know, he loved playing football with his mates – but afterwards his feet would just be such a mess, and he wouldn’t be able to play for a while. That was his choice – and it didn’t stop him from playing. He wanted to do all the ‘boys’ things – but they meant it would make his skin bad.”

I remember Mark arriving at our house covered in bandages after coming off his bike – and he still wanted to play footy! Somehow, I never saw him without a smile on his face.

Mark Lowe on sports day

The smallest of impacts can cause a blister or rip the skin. Mark’s school even gave him a computer to work on – this in the mid-90s – because he couldn’t hold a pen due to soreness in his fingers. “They’d give him extra time in exams because it took him longer to get through it,” Auntie Di says.

She didn’t play football herself but nevertheless spent her own childhood swathed in bandages. “It wasn’t ever so nice because people would point at you – but I went to an ordinary school with it. I think it’s just something I’d got, and I got on with it.

“I can’t really walk far. If I walk on uneven ground, it just makes my feet blister. I’m still bandaged up – I’ve just learned to live with it. People I’ve met through time have obviously noticed that there’s something different with me. I’ve got no nails on my fingers; I’ve got no nails on my toes.”

The first day

When Mark was born, it didn’t take long for her to realise that he had EB. “I covered his hands up with mittens: I don’t know if I was trying to hide it from me, or from him,” she recalls of that day more than 40 years ago.

“I’d had Emma, and she hasn’t got it. There was a one in two chance of him having it. It was awful. I thought: ‘I’ve passed that on. I’ve done that to him.’ Not that he ever held it against me or anything; but it was worse, I think, than actually having it myself.”

Sadly, our Mark passed away 20 years ago following a second battle with leukaemia.

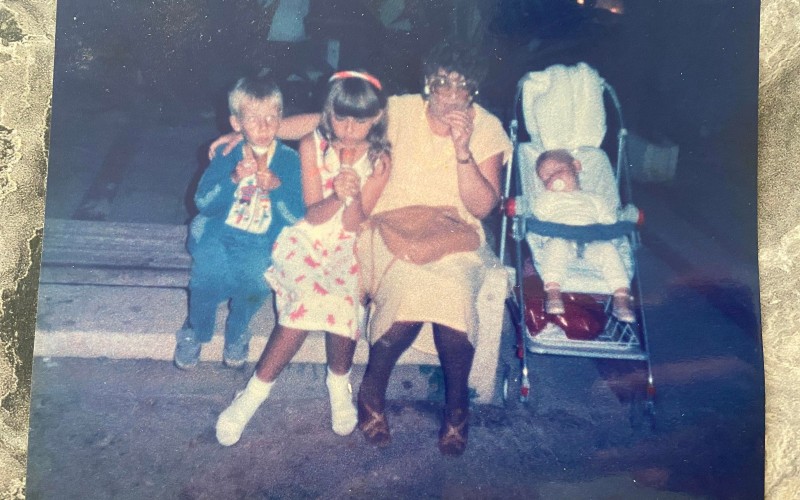

Mark, Emma and Diane Lowe

I have an abiding memory of my family running a half-marathon in Mansfield to raise money for DEBRA, ‘the butterfly skin charity’ which supports people with EB (and my injured dad limping to the finish line).

Auntie Di and one of her two sisters – who also has EB – receive support from the charity to this day. “I was never in touch with DEBRA while Mark was alive. Because we were coping with it, we didn’t really want to involve anybody else. But I’m really glad we have now.”

She explains: “We got in touch because they stopped making an antibiotic ointment we used so we’d got nothing to put on our skin. They gave us new ointments and lots of other things as well. If we can’t get dressings, they send them through the post. They’ve been absolutely fantastic.

“It’s nice to know you’ve got somebody you can ring and they’ll be there and do what you need.”

A lifetime of support

Dr Sagair Hussain, director of research at DEBRA, says the charity has two main roles: researching a cure or treatment for EB, and community support.

“We are there from the moment that a baby’s born with EB,” he tells me. “We provide guidance and support to mums and dads: how do you pick up a baby that has got fragile skin? It’s not the easiest thing to do.

“As a child grows up, we will go into the school to educate them on their needs. If they have blisters on their feet, they can’t climb stairs – they need to stay in a classroom on the ground floor.

“In a job, one day they may be operating normally; the next they may be in a wheelchair and their employer might wonder why they cannot go into work. We educate them around this, explaining how they have a valuable employee and need to adapt the work environment to help them.

“In the most severe cases, when people can’t work, we help them with their benefits. There’s a lack of awareness around EB – when you go into a job centre and tell them about EB, they’ll say: ‘I’ve never heard of it.’

“There are roughly 5,000 people with EB in the UK. You’ve got the really mild and the really severe end. At the severe end, as soon as that baby’s born, you know there’s something wrong. Diagnosis is really quick: they’ll get referred to the EB centres, which will say: ‘go talk to DEBRA – we can give you that clinical support but what you need is that community home support’.

“We provide support at every single stage of life, all the way to the end.”

If you can spare anything, support DEBRA by sponsoring Jonathan’s run here

DEBRA helps to fund national EB centres where specialist nurses and doctors provide a variety of care from dermatology to podiatry, dietary help and even dentistry. “If somebody has a severe type of EB, their oesophagus can blister: we help them to eat what they need to maintain health,” says Dr Hussain.

Auntie Di and her sister visit one such centre, in Solihull, twice a year. “We go to a special dentist because we get blisters in our mouth; we also have a podiatrist who keeps an eye on our feet. They’re absolutely marvellous.

“It’s not always easy to explain to people what it is we have. Not long ago, I got a piece of gammon stuck in my throat because EB affects your swallowing. I had to go to A&E and they couldn’t get it out – I could breathe, but it wouldn’t move. I told them about DEBRA and they got in touch – in the end they had to put me under anaesthetic and take it out.

“When I eat, I do have to be really careful: I choke quite a lot, but that was the first time I’ve ever had to go to hospital. I don’t eat gammon or steak anymore!”

She adds: “When I had my heart attack, we went to DEBRA six months later and they said ‘why didn’t you tell us about this at the time?’

“It might have nothing to do with your skin, but it’s your body and it’s all connected. They want you to keep them informed because they want to know about all of you – not just your skin.”

New treatments

Support is focused on wound care and symptom management, Dr Hussain explains, as there are no approved treatments for EB. However, there are now two treatments in the pipeline.

One is a gene therapy targeting a small number of dystrophic patients with a particular gene mutation; the other is Filsuvez – developed by Amryt Pharma – an anti-inflammatory gel that people put on their wounds to promote healing.

“We’re hoping Filsuvez will be approved this year,” says Dr Hussain (pictured below). “Your natural body’s defence to chronic wounds is to kick in the inflammation – but these people have chronic inflammation all the time. Inflammation actually becomes part of the problem, rather than part of the solution.

“This gel brings down all the inflammation and allows the body to repair itself.”

The lack of progress in finding a treatment over the last few decades is down to the relatively small number of people suffering with the skin condition. “The reality is that it costs hundreds of millions of pounds to develop new treatments,” says Dr Hussain. “So for EB, we are looking at repurposing drugs that are already used in the NHS.

“We’re looking at anti-inflammatory drugs from psoriasis and eczema. We’ve got 20 drugs on our list, and have found the top four or five that we would like to prioritise – it’s now about starting clinical trials to show they’re effective. We’ve got some initial results to show that they work.”

A Life Free of Pain appeal

DEBRA’s A Life Free of Pain appeal aims to raise £5 million by the end of 2023 to enable the clinical testing of these 20 drugs.

Dr Hussain gives an example of a woman, aged 23, with severe EB. “She’s been put onto this one drug that’s already out there, and found that her wounds have healed up. She told us that she used to be on 19 painkillers, and now she’s on just three.

“She’s gained independence. Like your cousin, she used to spend three hours each morning putting bandages on; the wounds have healed up so much that she now spends half an hour on the bandages. She’s got almost two and a half hours back for herself; and her mum, who helps her, has also got two and a half hours back.

“We know these drugs work now; things are moving really fast in the EB space.”

He adds: “We are wholly reliant on volunteers and donations for our funds. Without those people, DEBRA wouldn’t exist – and we wouldn’t be able to do any of the things we’ve talked about. It’s absolutely essential, it really is.”

The Boy Whose Skin Fell Off

Events like the London Marathon are critical to boosting awareness of DEBRA and EB. Yet perhaps the most influential moment was the airing of Channel 4 documentary The Boy Whose Skin Fell Off back in 2004.

Telling the story of Jonny Kennedy, who invited producer and director Patrick Collerton to film the final few months of his life, it won an Emmy Award for its portrayal of the brutal reality of living and dying with severe EB. When I was trying to think of a headline for this blog, I had to pay homage to Jonny and Patrick.

It is an honour to play a small part in raising awareness – and hopefully a few pennies – of EB and DEBRA. It is also an honour to run London in memory of my cousin Mark, and in support of my Auntie Di. I only wish he could run it with me.

You can sponsor Jonathan’s London Marathon run, supporting his chosen charity DEBRA, at this page.