A crucial skill in the workplace is that of problem-solving: the ability to analyse an obstacle and figure out how to bypass it.

Many of us acquire this ability through years of experience. So why is it not taught as a fundamental part of our education?

It is a question Ian Livingstone CBE has pondered for many years. “Learning should be about empowering kids, not turning them into passive receptors able to regurgitate stuff that you’ve told them. It doesn’t work: they’ll forget that stuff,” he tells BusinessCloud.

“When you’re next flying across the Pond, think about how the pilot learned to fly. Would you prefer that they learn by reading a book, or using simulation software? Do you want them asking ‘Now what was that I read on page 23 again?’

“Using simulation software – effectively a game without the scoring – is a way of using our hands to get an engagement, which is critical in learning. And that seems to have been forgotten about in traditional education.”

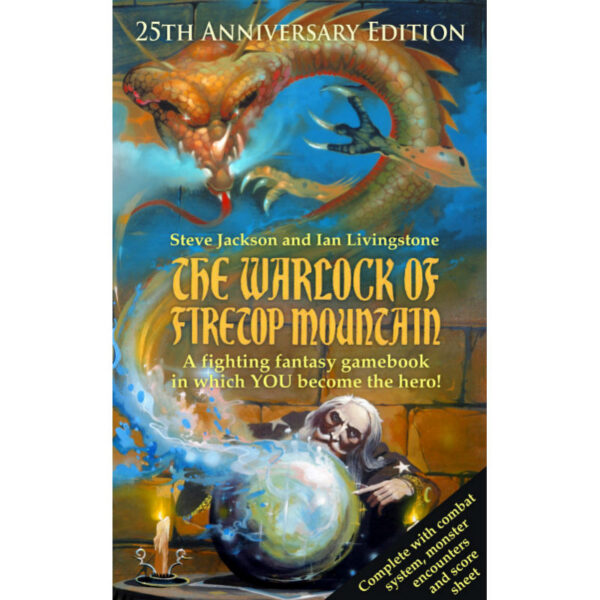

As co-founder of Games Workshop in 1975, Livingstone launched the infamous Dungeons & Dragons and Warhammer board games in the UK. Also the author of 15 Fighting Fantasy gamebooks – which sold around 20 million copies worldwide – he has seen the value of ‘learning through discovery’ first-hand.

These ‘choose your own adventure’ books, which I devoured myself as a youngster, gave the reader the chance to choose their own destiny at every turn – which often led to their doom.

“I like the social interaction of games and to learn through solving problems,” he explains. “After we launched the Workshop, we used to run ‘games days’. A book editor at Penguin, Geraldine Cook, was amazed to see thousands of people playing D&D and asked if we would write a book about the hobby.

“Rather than doing that, we wrote ‘The Warlock of Firetop Mountain’: a book to give people that same feeling of playing the game. It was the very first branching narrative book, with a game system attached, and it didn’t sell very well at first. Then we appeared on Radio One, reading out the options and encouraging children to phone in with their choices – and suddenly it went absolutely ballistic and sold out everywhere!

“Because they were interactive, they were empowering: they gave children agency. The multiple-choice system allowed them to play in many, many ways, and fail – but they would then want to start again.”

He adds with a smile: “At first, they were criticised because they were called Fighting Fantasy ‘gamebooks’: the word game always sends people into an apoplectic frenzy because they think children are doing frivolous things rather than using their time constructively.

“There was an eight-page warning guide put out by the Evangelical Alliance which said that interacting with demons in the books was bound to see children become possessed by the devil! And a worried housewife in deepest suburbia phoned a local radio station to say that, having read one of my books, her child levitated. The kids were thinking, ‘for £1.50, I can fly?’

“But teachers were beginning to understand the value of these books – they enabled critical thinking because children were trying to find the optimum way through the book. They increased literacy, they found later, by nearly 20%, because children really wanted to understand what each word meant, because it had a significance.”

Livingstone then got in on the ground floor of the UK’s video game industry, which witnessed a meteoric rise in the 1980s. He would serve as executive chairman of legendary developer Eidos from 1995-2002, launching the 75 million-selling Tomb Raider franchise.

“Through the whole period I’ve been in video games, there’s always been the sense that games are in some way trivial at best and probably harmful for children,” he reflects. “It’s now slowly beginning to dawn on people that games are not just entertainment; they’re powerful and positive tools in multiple ways.

“You cannot get through a game without problem-solving – it‘s impossible. You learn the game intuitively, through trial and error. There’s no such thing as failure – you’re not punished for making a mistake, you’re encouraged to try again.

“Minecraft, for example, is a wonderful creative tool, a kind of digital Lego, where children build these wonderful 3D architectural worlds and share them with their friends. RollerCoaster Tycoon is effectively a management simulation: design a theme park, understand the physics of the rides you construct, set the prices and staffing levels. If you do it right, the virtual customers will come to your theme park. If they don’t, you’re not wrong – you can just tweak the parameters until you have a successful theme park.

“Anyone can become successful over time. There’s no sense of feeling ‘I’m a failure’; whereas an exam is an arbitrary moment in time where, if you don’t answer a question right, you’re less able than others. That sort of standardised metric used to assess children, to my mind, is wrong. Children develop at different speeds – so why not let everyone feel a sense of success rather than being judged as failures early on in life?

“We see Generation Z being bored or fidgety in class, and some of them suffering with anxiety, because they’re taught in a very traditional way which goes back two centuries. Education has not kept abreast with technology.”

In 2010 Livingstone was asked to act as a government skills champion for the video games sector by minister Ed Vaizey. Livingstone described his resulting ‘NextGen’ report, co-authored with Alex Hope of visual effects firm Double Negative, as a “complete bottom–up review of the whole education system relating to games”. It led to the introduction of the computing curriculum in schools.

“We managed to convince the government to put computing on the curriculum to replace ICT, which was largely a strange hybrid of office skills – learning Word, PowerPoint and Excel – and gave children no insight into how to actually create their own technology,” he says.

“It’s a bit like teaching how to read, but not how to write: children need to understand how code works. They don’t necessarily have to write it – they could use middleware package, or Unity or Unreal to create content – but we wanted to put children into the driver’s seat of technology, rather than in the passenger seat, moving them from consumption to creativity.“

Far from satisfied, he is now putting his name to The Livingstone Academy in Bournemouth, part of the Aspirations Academies Trust which runs 15 schools across southern England. Set to be opened in September 2021, it is a science and technology academy for children aged 4-18.

Redevelopment of former police station and court buildings will hold 1,500 pupils

Steve and Paula Kenning, CEOs of the Aspirations Academies Trust, are former headteachers who found a kindred spirit in Livingstone. “We’ve worked with more than 50 companies and, invariably, they can’t find young people with the right skills for jobs. They have good qualifications in standardised tests, but they can’t think for themselves: collaboration isn’t there, creativity isn’t there, critical thinking isn’t there,” says Steve Kenning.

“We want our kids to work with employees at these companies as part of the learning process. We particularly want to speak with tech and video game companies about collaborating in this way.

“We are trying to develop more project-based learning, using computational thinking, to engage kids and challenge them. We’re linking subjects together: when you make a game, you’ve got artists, musicians, entrepreneurs, game designers. There are a host of different disciplines.

“We want them to go into the world of work with a different mindset, as problem-solvers and really good citizens for the future, and also happy – because there are well over a million kids who are currently unemployed because they haven’t got the right skills. It’s a big issue.”

Livingstone adds: “[The students] will be using games as a contextual hub for learning. How can you gamify the curriculum through projects, computational thinking, computer science, to give children agency for fun, understanding and knowledge? A qualification is nice to have, but what I’m more interested in is your portfolio – what you’re actually able to do.

“Digital literacy is almost on a par with literacy and numeracy. Computer science, you could argue, is the new Latin because it underpins the digital world in the way Latin underpinned the analogue world. For children to be citizens of the 21st Century, they need to know how this stuff works; otherwise they’ll just fall further and further behind as the world is transformed beyond recognition by technology.

“If you get them thinking this way very early on, the [resulting] transferable skills will enable them to make a game; work against cybercrime; design a jet propulsion engine. Our creativity is the envy of the world. I cannot understand why the government is intent on judging one child against another and stripping creativity out of the curriculum – it‘s insane! What we have in the UK is an intangible asset that is world-beating. It would be a sad loss if we were not the most creative nation in the world any longer.

“I did badly in school. It was a pretty miserable experience – and I think learning should be a joy. If I can leave a legacy [to say that] learning can be fun and that games are actually good for you – the power of play beyond entertainment – I‘ll be very happy with that.”

Ian Livingstone and Steve & Paula Kenning are interested in hearing from any tech or video game companies keen to collaborate and make a positive impact upon the curriculum. Please email stevekenning@aspirationsacademies.org

Video games