Drone delivery is the long-promised alternative to delivery by scooter, car and van. But it has yet to materialise as an everyday alternative.

Last year Uber completed proof of concept tests in the US which showed that food delivery was at least possible, but the service is still not available to its users.

Even further back, Amazon’s Prime Air promised the delivery of small items via its own fleet of drones. Operations were expected to begin in some cities starting late last year, but again the service has yet to materialise.

Since then, food delivered by drone has remained largely the work of PR stunts, which are much easier to organise.

However an Irish-based Thai food chain is going all-in on drone delivery, planning to have customers receiving their food by air in the next year within Ireland, and shortly after that in the UK.

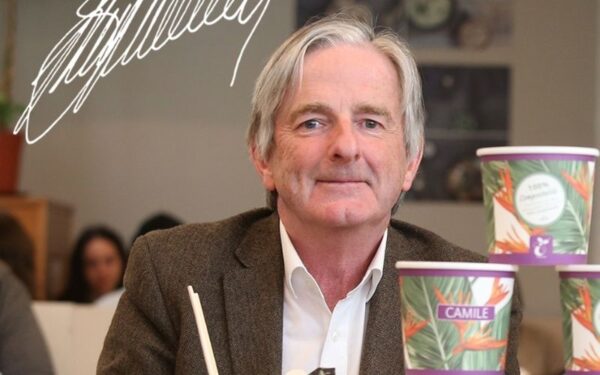

“Ours is definitely not promotional,” said Brody Sweeney, founder of Camile, the UK’s fastest growing Thai chain and a firm now looking for €10m backing to help fuel this tech ambition.

Sweeney was the man behind the O’Briens sandwich cafe chain founded in Ireland in 1998, which operated in 16 countries before going into liquidation in 2009.

He started Camile in 2010 as a ‘fast casual’ Thai food chain focused on health and sustainability. The brand is now operating in most Irish cities, Belfast and London.

Its investors include Web Summit founder Paddy Cosgrave, Bobby Healy – founder of Manna, Europe’s first drone delivery tech company – as well as senior partners in Draper Esprit.

Sweeney says the brand quickly adopted tech to manage the logistics of its kitchens, helping it to keep up with larger-than-average order volumes.

Unlike a normal restaurant, Camile kitchens service their 30-to-40-seat restaurants while also fulfilling off-site app orders, which can be up to 80% of the day’s activity.

This model is why the restaurant has survived COVID-19 lockdown as it adapts to becoming entirely off-premises.

“It’s been good for us,” Sweeney says of the lockdown. “We’re in suburbs and we do home delivery. That’s the only game in town in food service at the moment.”

Well-established in Ireland, and with ambition for the same prosperity in the UK, over the last three years Camile has established locations in South London where sites are currently in development.

Sweeney said the opportunity for home delivery via a dedicated restaurant app was only offered by pizza brands in the UK. Camile’s plan is to do the same with Asian food.

“You’ve got good Asian brands in the UK like Wagamama, Yo Shushi! and Busuba in London, but nobody’s focused on the home delivery side.

“It’s an amazing opportunity because it’s not just the UK, there’s nobody in the States who’s focused on that either.”

While Sweeney recognises the well-established third-party delivery apps such as Deliveroo and Just Eat as a vehicle for delivery, he says the strategy has always been to avoid them – and now to beat them to customers’ doors with a drone.

Commissions for these food delivery giants range from 20% to nearly 40% of sales, he says. After the costs of food and labour, Sweeney says there was no margin left for the cost of these aggregators, but recognised the risk of not appearing on these platforms now that they are well understood.

In Ireland Sweeney estimates around 80% of business is done through its own channels, helped by having established the brand and app before Deliveroo was even founded.

“It’s really the big challenge for us, not to be too dependent on Deliveroo or Just East because the business isn’t viable if we are.”

In London, where the firm has six sites, it is closer to half of the business, but Sweeney hopes that will come down, in part with the help of drone delivery.

Brody Sweeney

How Camile’s drone delivery will work

Camile’s drone delivery is being provided in partnership with Dublin-based drone firm Manna. When the service is live, users of the Camile app simply select a square on Google Maps to which the food should be delivered.

The food is cooked and loaded into one of the drones, which live on a shipping container set down beside the restaurant.

The drones take off to around 400ft and fly at around 80kph to the allocated space.

A text message lets the customer know that the drone has arrived, at which point it drops to 40ft and the food is lowered on a piece of biodegradable string. “The technology works perfectly,” he says of the firm’s extensive testing to date.

Not only that, but it’s cheaper, faster and more environmentally friendly.

Drone delivery costs about half that of a delivery driver, can fly in 90% of weather conditions and has no emissions, which Sweeney says makes it a ‘no-brainer’.

He said these drones could complete around 80% of the deliveries currently made by traditional transport.

People in London can expect the service in around two years, as it begins in the relatively easier to serve suburbs and works its way inwards.

But there are caveats. Houses without a private outdoor area to land, or those which sit on public streets, are unlikely to get the service, and those in flats would have to live in a building with a landing pad.

Flight planning may also become a sticking point in future, says Sweeney. Drones currently have to meet the same safety requirements as a commercial jet.

While in testing Sweeney says getting clearance for a flight path from the Irish Aviation Authority is easy, but when there are thousands in the sky it will get more complicated.

But Sweeney is confident that drones in the sky will quickly become commonplace, and once the logistics of aviation clearance are automated, he believes other authorities will quickly fall in line.

Prior to the pandemic, Camile’s plan was to have drones in operation by the end of the year, but Manna switched to supporting Irish health services with delivery of prescriptions.

Sweeney predicts the operation will now be live in around a year’s time. “It won’t work for every site, but it will work for most of them,” he says.

Those hoping to get a drone delivery will need to live no more than two miles from one of these sites, which is already about 95% of the firm’s delivery business.

“They are coming. There’s no question about it,” he says. “Drones are built to deliver food. The typical payload is about 2kg, which is perfect for a drone.”

While being first to market with established drone delivery will no doubt create a buzz, Sweeney thinks that once the model is proven, consumers can expect to see the service become commonplace, and even routine.

“I don’t think 10,000 aircraft in the sky is a problem, that’s just a computer working out flight paths. And there’s no security issues because they don’t carry cameras, so there’s no videotaping over people’s properties,” he says.

The drone’s two-mile radius does mean more locations are required if the brand is to meet its customers via the sky. The firm is planning further expansion in the UK, which it will do via the take-over of failing pub kitchens, and experimenting with ‘cloud kitchens’ – purpose-built to produce food specifically for delivery.

The firm will also look to bring robotics into the cooking process, resulting in even more automation from the point of an order.

“Cooking on a wok for us is a repetitive task, it’s mechanical. We’re trialling a version of a mechanical wok, and we think that we’ll be able to redeploy staff away from cooklines into doing other things,” Sweeney says.

The brand, which found the start of lockdown “hairy” while trying to encourage staff to come in to work, was cognisant that if it was less dependent on employees it would make their job “a little bit easier, because we’re not dependent on people showing up if we can mechanise it in some way”, he says.