The internet holds a range of information which can identify us – from personal details to the choices we make online.

But do we know the extent to which we are tracked? And should we be keeping a tighter rein on this valuable commodity?

Data creators should also profit

Every click you make online generates a piece of data specific to you. Every choice you make is tracked by companies you’ve probably never even heard of, with the information generated sold on.

The moves we make online become part of our digital fingerprint – and companies are making money from this.

As an example, Enfield Council in North London allows 25 different companies to collect your information when you visit its website – seven of which are data brokers, whose business is selling your data. The result visible to us is tailored adverts – which we’re all familiar with – but it is someone else who is making money from the fact that you’ve seen a particular ad.

London-based Sam Jones (below) believes this scenario needs to change. He founded Gener8 to enable individuals to become the ones making money from their data.

Sam Jones

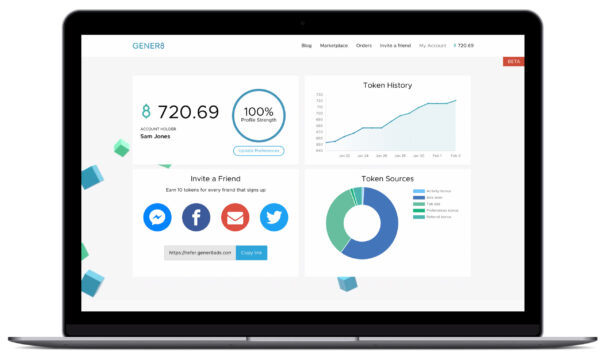

Gener8 Ads is a browser extension that enables you to control and earn from your own data.

It tailors the ads you see online, blocks third-party trackers and anonymises your data, if you wish, to be used for custom research. Gener8 Tabs is a browser extension that allows the user to earn every time they open a new tab and Gener8 Sentinel helps you see if your data has been breached.

Gener8 ads

Jones has also launched the Digital Data Dividend petition, calling on the Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport to table a legislative motion that ensures UK citizens can share in the wealth created when companies process and sell their personal data.

“Everyone has a different perspective on data and I’m not saying that your data being out there is good or bad, but I believe people should have the choice,” Jones, who spent seven years on the global marketing team for Red Bull, tells BusinessCloud. “If a person’s data is being monitored and sold then they should have the right to share in the wealth.”

Jones says to hide your online actions is currently a complicated process. “Right now, if you used the world’s largest search engine and you wanted to opt out of your data being tracked, it would take you 17 clicks to do so. The average person doesn’t have the time to do that.”

Explaining how it works, he takes the example of the council website. “If I went to that website and clicked on the option for disability services, then they’d sell my data to a business concerned with disabled people’s services. It’s absolutely mind-blowing – and similar things are happening across the majority of websites.”

Gener8, which is a passive service, has 75,000 users in the UK – a figure growing by 10,000 every month – and says they earn £5-25 a month. Jones is aiming for a million users by the end of 2020.

All data can be used against you

Gal Ringel, co-founder of Israel-based Mine, turns the questions on me during our interview – “as an EU citizen, have you ever exercised your GDPR rights and would you know how to do that?”

The answer is no – and it’s a common problem Ringel and his two fellow founders, who met while working in Israel’s military intelligence services, are aiming to solve with their tech business.

While working in their country’s equivalent to MI5, the trio dealt with personal data and saw how easy it is for this to be exploited. “GDPR regulations are highly complex for the average person, but it’s important for people to understand their personal data and be able to control it,” says Ringel.

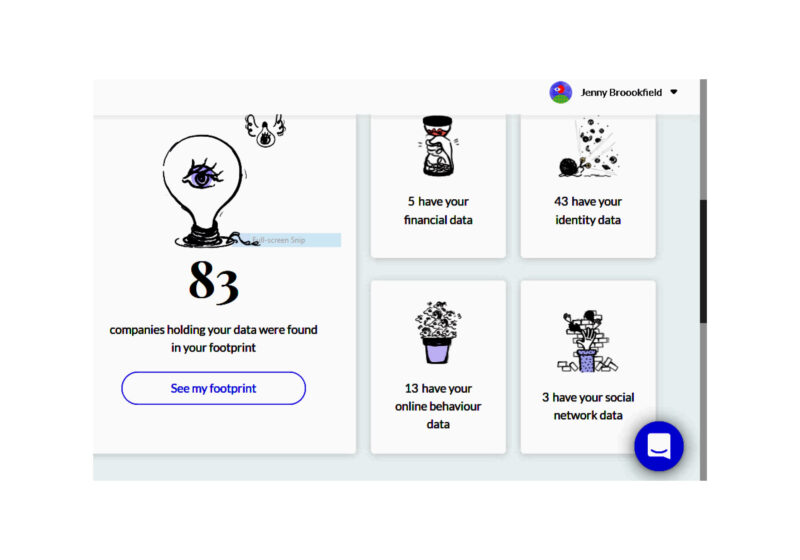

The result is Mine, which works by scanning a user’s email inbox using AI to discover which businesses hold their personal data in just minutes. Once your digital footprint has been produced, you can allow Mine to instruct that business as to whether you want them to stop holding your details with just one click of the mouse.

Mine app

A person’s footprint grows by an average of eight companies per month, making it highly dynamic in the modern connected world. Ringel spoke to us not long after the UK had gone into lockdown and warned that the coronavirus situation would see these figures grow even more.

The dependency on technology tools while in isolation for online shopping, home working and entertainment means people were increasing their digital footprint by more than 50 per cent.

But why does this matter? “All data can be used against you in any way, whether it’s ID theft, reputational damage, financial loss or manipulation – that’s any data that’s related to you as an individual, whether it’s your full name, home address, date of birth or financial information,” he says.

A lot of what we do online can be a one-off, he says, for example purchasing a gift from an online retailer. If that retailer is hacked, the details they have from the purchase you made then fall into the wrong hands.

“British Airways was breached last year and we find that for every user there are 12 data breaches they weren’t aware of,” Ringel adds, adding that the business has had 40,000 sign-ups who have made more than 250,000 ‘right to be forgotten’ requests since it launched in January 2020.

Is your data protected?

The UK is behind markets like the US when it comes to cybersecurity, with the prevailing attitude of “it’s not going to happen to us”.

That’s the view of Perry McShane, sales manager of Leeds-based InsurTech business CPP Group, which helps businesses and individuals fight online identity theft.

“People are lax and tend to have one password they use all over the place, but once someone finds out one piece of information about you it’s likely they’ll be able to get into other aspects of your life,” he says. “It’s the same in the business world. Small businesses don’t tend to buy cyber insurance because they assume it will happen to the bigger guys.”

McShane admits he had a similar mindset before joining the business and running Owl Detect, one of CPP’s products, which monitors data to combat online identify theft. For a monthly subscription, users can enter debit or credit card numbers, bank account details, email addresses and phone numbers, passport details, national insurance number and driving licence number.

The process runs a historical search of your data against a database of compromised personal data, collected for more than 10 years from unsecure and illegal data trading sites. It then continuously scans the web, including illegal websites and the dark web, for consumer and business data that could be for sale or in use by cyber criminals.

If a breach is found, the user gets an action plan on how to prevent it happening again. CPP’s second product, KYND, protects small businesses from cyberattacks, scanning their website and producing a traffic light system report listing all the cyber risk exposures in amber and red, and then offering security advice.

With some individuals, there could be a feeling that things will be fine because they’ll be insured if their credit card is used fraudulently – for example – but McShane warns that people should be more concerned about the loss of data that actually led to that cash being spent and the efforts to get it back.

In the US, most people have personal cyber insurance, but similar products launched here have failed to make a big impact because of people’s attitudes, he says. Similarly, businesses tend to think they are watertight.

Advice afterwards can include embedding a ‘honeypot profile’ into your customer database. If there’s ever an email from that customer, you’ll know there’s been a breach. “People and businesses are nine times more likely to be involved in a cyberattack than become the victim of a burglary, and yet while we’re happy to have appropriate buildings insurance, we don’t think about cyber protection,” he adds.

Educate people to value their data

Better education is needed around data security to ensure people bring good practices from their home life into the workplace, and vice versa.

George Gerchow is chief security officer at San Francisco-based Sumo Logic, which manages vast volumes of data for companies like Adobe, airbnb and Pokemon. He is in charge of how the company manages processing data on behalf of customers, and must ensure it is compliant around keeping data private and secure.

“With the amount of data people share about themselves on social media – celebrating birthdays, kids’ names and pet names – I would have no problem working out someone’s passwords,” he says, adding that it can often be a generational problem. “A lot of younger people are willing to put everything out there, which puts them in a compromising position. People take these personal habits and bring them into the workplace with them, which is where businesses need to be careful.”

He gives the example of making a purchase from a shop and giving your postcode, email address or telephone number at the desk for receipts to be sent to you or to join a loyalty scheme. Then there is sharing your location, posting pictures of a passport when you go on holiday or showing your driving licence when you pass your test. “People give up that information so easily so it’s readily available, but hackers have no mercy and they’ll go after a person’s or business’ identity no matter what the current climate is,” he says.

Businesses need to make data a priority, starting with understanding what their sensitive data is before drawing up data handling and retention, and data encryption, policies.

“Employ best practices to safeguard your data,” he says. “People aren’t educated and that’s where it starts so a combination of education and tools is a worthwhile investment. Businesses should consider employing a data protection officer who’s responsible for awareness and handling of data along with policies around data. With that kind of education at work, your employees might transfer that knowledge to their own personal life.”

Smart companies are handing back control

Gilbert Hill

Bristol-based Tapmydata is a free app to enable people to discover what companies have their personal data, ask about it and keep it safely on their phone, along with their identity details.

It’s then up to them whether they choose to share some of their data with groups they trust (environment, voting rights, gambling aware), or to offer it up for sale, on their terms. Chief executive Gilbert Hill agrees consumers should have the right to benefit from their data and take better control over it.

“It’s very difficult to value our data, as it’s not clear what all the players and intermediaries make from it,” he says. “Smart companies realise that people are concerned because they feel businesses get all the action in the data ‘deal’, and have lost control of their personal information.

“Brands like IKEA are going beyond legal obligations, providing tools like preference centres for users and repatriating questions about data back from legal to the core areas of the businesses who know how to answer them as part of a customer dialogue. This may kickstart the ecosystem for people to really get agency (and cash) from their data.”