The fashion industry is notoriously difficult to predict despite the data revolution sweeping other sectors.

Trends quickly take a hold and, as suppliers scramble to service the newfound demand, can again become redundant within a few short weeks.

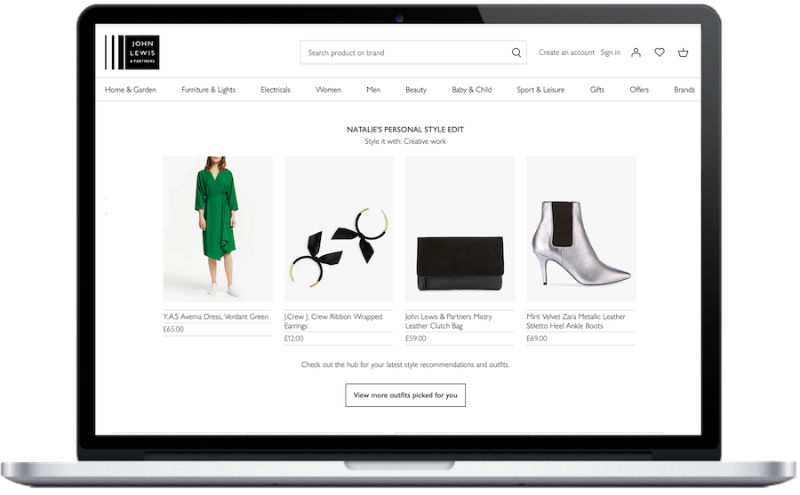

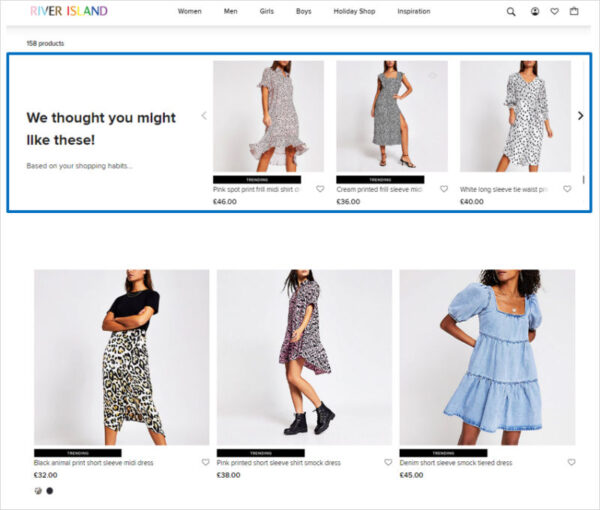

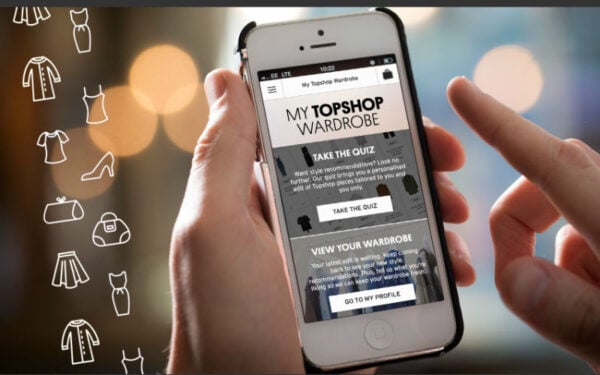

Enter fashion prediction platform Dressipi, fifth on our recent London Tech 50 innovation ranking. Co-founded by Donna North and Sarah McVittie around 2012, the business is working with high street brands John Lewis, River Island and Topshop to help them predict what customers will buy and not return.

“Fashion and clothing is much more complex than most other products,” North tells BusinessCloud. “Every product has a very short lifecycle, only about six to eight weeks, and there is always a ‘cold start’ problem.

“The physicality of the consumer makes a real difference as to whether they can wear that item, from a size or shape perspective; then you get into their preferences; and then there is the context.

“So there are a lot of challenges that prevent you from taking off-the–shelf models or algorithms and using them within the fashion domain.”

And North should know. With a strong background in digital media, the entrepreneur – who will speak at our free virtual event on fashion tech (click below to register) – was “early to tech” in the 1990s.

https://businesscloud.co.uk/events/meet-the-fashion-tech-trailblazers/

At IMG she oversaw the creation of technology to enable new business models, digital rights and content across the media giant’s portfolio, including for the International Olympic Committee and football federations.

“It’s not very well known, but IMG had a very big investment in fashion and modelling agencies. That’s where the idea for Dressipi first started,” she explains. She teamed up with McVittie – a former city analyst who had sold her text message question answering service Texperts to the owners of 118 118 in a multi-million-pound deal – to found the start-up.

“As more and more retailers went online, we could see that there was a big problem around navigating choice. Dressipi initially tried to solve that problem: how do you edit down from a million available players to the ones that are the best match for the consumer?

“The volume of data needed to build smart algorithms effectively forced us very quickly to move the business from a B2C model to B2B, as that enabled us to start getting access to volumes of transaction and activity data and build the smarts.”

Dressipi now claims to hold the largest and most accurate customer and garment dataset in the industry, powering billions of product and outfit predictions every year. River Island says customers who interact with its personalised content are twice as likely to convert to a purchase, while their average order value increases by an average of 20 per cent.

A team of 25 today, it employs mostly data scientists and engineers who work with experts to gain that crucial human insight into fashion.

“Very early on, we paired our data science and engineering teams with fashion stylists so we could learn and implant those kind of nuances into the algorithms,” says North.

“If a product type suddenly starts getting bought, a stylist might say ‘that became a trend three weeks ago’. Suddenly customers who said that they didn’t like polka dots and flares last month are going to purchase that item.

“No one other than somebody close to fashion will be able to pick up nuances like that, which are the small percentage difference in performance from a pattern perspective.”

Up to 40 per cent of clothing bought online is returned, compared with 5-10 per cent of in-store purchases. “If you’re just looking at the data and seeing a pattern of returning that is illogical, a stylist might be able to say, ‘the reason that item is being returned is the neckline is very high – and if you look at the consumer base that are returning, they’ve all got very large bust size’.”

Every product is attributed a set of 25-50 data points to create a ‘digital twin’ of every feature of a garment. “For example, there could be detail on the bust, transparency on the back,” says North.

“We may then combine features to get a trend. If polka dots and flares combined with a certain material make a trend, then we can annotate every garment with that set of features. Then when it starts behaving differently to how we may expect, we would understand why that is.”

According to North, another problem unique to clothing is that around 40 per cent of products created are never sold at full price – and therefore are oversupplied.

Identifying true demand is also tricky. “A retailer might sell out a product very, very quickly in a small number of core sizes. It is then a ‘fragmented product’: they can no longer promote it so it is hidden and it becomes very difficult for a customer to get to that product thereafter.

“If you use personalisation on the front end – getting customers to products as quickly as possible that best match their needs and their preferences – then you have a view on what is true demand. And then you can start solving the supply side: what supply do I need for that true demand?

“The two sides are symbiotic: we come in at both ends.”

North, left, with McVittie

COVID-19 saw a shift in online purchasing habits from evening wear such as dresses to more casual clothing. “Our retailers saw a big shift in what the consumer was purchasing. We also saw a big shift in their need to have more nimble access to their data,” says North.

“We built data products which enabled them to get a view in real–time about what was going on in their business so they could access the insights they needed to react in the moment.”

The company has mostly focused on the UK but counts OVS, the largest fashion retailer in Italy, among its clients. It is soon to announce clients in other countries, with European, Australian and US expansion on the cards.

The question of sustainability is also firmly in the founders’ thoughts. “Fashion is responsible for about 10 per cent of global carbon emissions. Part of what excites us around making the supply chain more efficient is this ability to reduce wastage in the system,” says North.

“In fashion the margins are very, very slight and it’s moving very, very fast. It’s very difficult for these retailers to stop and take a step back and say, ‘Okay, how can I do this differently?’

“The way to tackle some of these issues is to help them improve their profitability; get rid of some of the wastage; create more optimum inventory in supply chains; then that frees up a little bit more profitability and time to then really start looking at this huge problem.

“It’s very difficult to solve it when everyone’s breathing down your neck and you’re a low–margin business.”